Maybe the Grid has been more stable lately, or less stable, or maybe there’s one of those collective deep breaths as the community waits for, well, whatever it waits for – the next CSI build? The next Burning Man? The first pronouncement from Governor M. Or Agent M. Or Organic M.

Smoke puffed from the upper windows of the Lab, black and filled with morning, and then the white smoke told us that He Had Been Anointed and now we’re all waiting for his appearance on the balcony.

And in the idle time we wonder whether M will play Medvedev to Rosedale’s Putin (OK, sorry, mixing up metaphors), or we start to wonder whether we should change our prim hair, it might be time again, or maybe we start wondering about all those 2D games we keep hearing about, or the happy hamsters over on OpenSim getting their own little grids up and running, and in the meantime some boorish newb has insulted our sense of propriety and we’ve got this feeling that the social norms have been upset and it’s time to reinforce the TOS.

So we end up with competing threads. On the one hand, virtual worlds like Second Life will fade away:

Second Life and it’s walled/closed ilk will fade into the sunset in the next 24-36 months….Look at the rapid progress towards standards with OpenSim and Sun’s Wonderland, and you can tell that walled garden virtual social worlds, even with all the great diversity of experience and creation, are one evolutionary step behind.

And on the other, the long-time residents of Second Life worry that social norms have been eroded and look to the Terms of Service (TOS) to help re-establish a sense of trust:

Tacit laws are difficult to understand, to share with newcomers and to spread across a large population. Tacit laws are also more prone to unfair balances in power and influence, which serve as particularly bad influences on new and emerging markets as those afforded by virtual worlds.

Now I don’t know about you, but I feel stuck. Outright written rules fail us, and tacit governance is nearly impossible if not unbalanced at scale. Where does that leave us?

I think it leaves us at the root, the elephant in the room, with that which is so ill defined that while we write laws around it, socially we embrace a tacit governance that allow us to rationalize our circumvention of legality in a case by case way.

That root, is trust.

Fragile Faith

Rheta Shan hits all the high notes in arguing that Second Life’s defining feature is its sense of immersion, because the disconnection from avatar and identity is no more than what’s possible on a mySpace profile:

Because 3D avatars make sense even if they are no more disconnected from RL identities than Facebook profiles are — the immersive sense of a place to be in, the intuitive simplicity of walking up to a person to strike up a conversation, the option to do things together nicely balance the disorientation and bewilderment its sheer size and lack of structure beget — and there are other advantages as well. As technical deficiencies become less, we can be sure to see this kind of social metaverse attract a larger audience, an audience to which the idea of disconnecting identities might be utterly outlandish.

Maybe we’re losing faith and it takes our seers and those with experience to remind us of the virtues and features that define the ‘platform’ in the face of all those other platforms, all those phone-based worlds, and gaming macro-sites, and Metaplace mini worlds.

The “brands” have lost faith – they’ve moved on to 2D worlds and places like Kaneva maybe, little phone games or banner ads in Grand Theft Auto. The learning curve is too steep, and they’re looking for the sweet spot between reach and time – some perfect combination of accessibility without losing the deep immersion, or at least big swatches of your calendar, they want to keep you up all night playing with their brands (in a nice tightly controlled way, if possible) and they want to make it easy for your friends to join up too without needing a 3 hour course on how to fly or attach your hair.

The stat watchers are losing faith – the uptick in new users is stalled, concurrency is barely, just barely, ticking upwards, and the number of premium accounts has dropped.

And the residents lose faith every time the asset server forgets to send their underwear along, or transactions are frozen because, well, “we’re just too busy right now”. Philip’s promise at the last SLCC was all talk and t-shirts and no discernible follow-through – wasn’t Havok supposed to fix things? Maybe Mono will? Hmmm…your shoe is in your ass, by the way, might wanna reattach.

We Have Come of Age

In his new book Coming of Age in Second Life, Tom Boellstorff documents the years he spent doing rigorous anthropological field work in Second Life and has produced a stunning monograph that may well one day rank as a milestone in the study of virtual worlds.

Tom’s job, being an anthropologist and all, is to look at the mundane and extrapolate its meaning to a wider culture. He devotes an entire section to the concept of AFK – something which I hadn’t thought about, something so embedded in the way of Second Life that it’s, um, second nature. From something as simple as AFK, from the modes of communication like IMs and public chat, he’s able to circle out into wider and wider meanings, and deeper and deeper insights.

Tom’s book is nothing short of revelatory, partly for being a solid piece of research, but more for the insights he comes to, and the argument he’s made that virtual worlds can be studied on their own terms – something that residents would nod noddingly to, but which is an important marker to the rest of the egg heads behind their ivy walls (oops, sorry Tom, don’t mean you, your head is far from eggy).

Tom looks at the Terms of Service, at changes to the code, at the role of the Lindens and comes away recognizing the impact they have on the community, but this is subservient to wider contexts, other meanings, other artefacts created by the residents, no matter how traumatizing the changes to policy or the code. He draws a parallel between the governance of Second Life and the shift from sovereignty to what Foucault termed “governmentality”, meaning a shift from a governance that was self-justifying to one in which it resided “in the things it manages…the instruments of government, instead of being laws, now come to a range of multiform tactics” (emphasis added).

Tom observes that “the company claimed to employ a laissez-faire mode of governance, which can be seen to reflect a “virtual governmentality” combining modern logics of governmentality, creationist capitalism, and the “Californian Ideology” that is predicated upon “an impeccably libertarian form of politics”.

These observations alone are worth the cost of the book. But it’s in his broader concept of techne that perhaps holds a hint for the future of Second Life, and other ‘walled gardens’.

Our Strange Loops

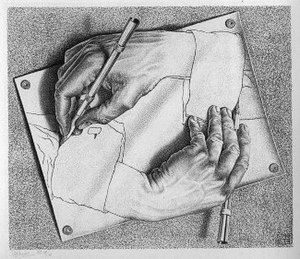

I love Tom because he helps to articulate my vaguely formed notion of Strange Loops and which was described by Douglas Hofstadter in his book I Am A Strange Loop:

And yet when I say “strange loop”, I have something else in mind — a less concrete, more elusive notion. What I mean by “strange loop” is — here goes a first stab, anyway — not a physical circuit but an abstract loop in which, in the series of stages that constitute the cycling-around, there is a shift from one level of abstraction (or structure) to another, which feels like an upwards movement in a hierarchy, and yet somehow the successive “upward” shifts turn out to give rise to a closed cycle. That is, despite one’s sense of departing ever further from one’s origin, one winds up, to one’s shock, exactly where one had started out. In short, a strange loop is a paradoxical level-crossing feedback loop.

Tom talks about personhood in virtual worlds and observes that for many, virtual worlds seem more “real” than the actual world (a term he prefers to real life, or the real world, because it also implies actuality and speaks to the gap between virtual and actual, an important finding of his studies):

The theme of Second Life permitting access to an interior self that in the actual world is masked by an unchosen embodiment and social obligations was common… Residents often linked these transformative possibilities to the experience of avatar embodiment. Avatars were not just placeholders for selfhood, but sites of self-making in their own right.

On this front he quotes a resident who said that “despite everything, who I am still seems to come out, so perhaps I discover my essential self through my avatar” and another who commented that “my offline self is becoming more like my avatar, personality-wise. It’s like SL has grown on me and looped back”.

He then goes on to examine the issues of alts and how they can “oeprationalize the gap between actual and virtual into a resource for fractal subjectivity, into a kind of “dividual” (rather than “individual”) selfhood for which persons are “constructed as the plural and composite site of the relationships that produced them”.

This fractal subjectivity deepens his insight into the idea that there is an instantiation of a discontinuous self – that there is a clear gap between where one alt ends and one begins. But that this gap is not exclusive to alts, but rather the very basis upon which virtual worlds are built.

“Such a gap,” he says “Is the product of techne, and a precondition for homo cyber, the virtual human.”

In Our Tools We Trust

I favour the idea of Second Life as a story box:

We hold fast to a social identity that we believe lends us a name and a face, but equally fast we move from one definition of a society to another, alternating again and again that presumed identity. Like characters in a story that keeps changing, we find ourselves playing roles that others appear to have invented for us, in plots whose roots and consequences escape us. ..Even when declaring allegiance to one place, we seem to be always moving away from it, toward a nostalgic image of what we believe that place once was or might one day be….and yet, partly because of our nomad nature and partly due to fluctuations of history, our geography is less grounded in a physical than in a phantom landscape. Home is always an imaginary place.

Tom echoes this sentiment, empathizing with the concept as an anthropologist because, after all, anthropological writings “are fictions in the sense that they are something made, something fashioned – the original meaning of fictio – not that they are false or unfactual.” But it is in this fashioning of stories that virtual worlds are representative of techne the counterpoint to which is episteme, or history, and reminds us of W.H Auden’s musing on storytelling and the notion of a secondary nature mediating the human: “man is a history and culture making creature, who by his own efforts has been able to change himself after his biological evolution was complete. Each of us therefore has acquired what we call a second nature, created by the particular society and culture into which we happen to have been born”.

And he draws attention to the idea that there is a lot to be learned about the interplay between the actual and the virtual but that much research on virtual worlds “is predicated on a cultural assumption that if a boundary is transgressed it is thereby blurred or weakened. However, a large body of anthropological work…demonstrates that crossing a boundary can strengthen the distinctiveness of the two domains it demarcates.”

He argues that virtual worlds are not unique because of their tools, because in fact humans have always been virtual – they have always used tools to move into the future. What makes virtual worlds unique, in his mind, is that we now have a tool we created in which we have tools for creation. Virtual worlds are an extension of the continuity in which humanity crafts itself through the gift of techne. (At which point, I should probably introduce a note of caution that Tom IS afterall from California, hehe).

Yet alongside this continuity of crafting ourselves through culture, there is change. In this age, “humans can, for the first time, create new worlds for human sociality”. This does not mean that there are not other technologies that allow this, but Tom posits that “at issue is simply that virtual worlds have unique characteristics and social significance that does not hinge on a direct relationship to the actual world”.

“In virtual worlds we can be virtually human, because in them humans, through techne, open up a gap from the actual and discover new possibilities for human being.”

My Avatar is Not Me

Rheta believes that my notion of the story box is primarily a collective notion:

Where he was wrong was in thinking the storytelling experience is collective. It is not. It is individual, even where the multitude of residents interacts. They interact because a story without an audience might as well remain untold. But the essential thing about this is that it doesn’t make a community out of the multitude. It’s a cacophony, not a campfire group listening to the griot.

And that gets us into the territory of whether we’re defined or whether society partly defines us, but sure, we’re not telling a group tale, our tales are our own. But we are formed because of our culture – and culture is about place, and it’s about our stories, and our artefacts, and it’s about the banal and mundane. It’s about what AFK means and how communication is different when we can both chat in public and in IM. It’s about my new couch or my house at the beach.

My avatar is my interface to a culture, and in this case, the culture in which my avatar performs (just as I perform in the actual world within my own culture) has the unique property that it’s recursive and that its basis is techne – one in which the tool we’ve built in silicon and wire contains the tools within it.

We can fret about other worlds, and we can worry about the sustainability of the cultural norms, but what’s unique about Second Life compared to say World of Warcraft is that is allows techne within it, rather than being simply performed there. Sure, there’s a culture in Wacraft, and you can fall in love, and there’s social norms and governance, but it’s stasis. It doesn’t embed the ability to move the human journey forward.

Facebook might be a culture, or it might be an indicator of a larger cultural change. And you can put little 3D rooms on your Facebook page or walk around with a little virtual room on your cell phone, and you can decorate your room and you can socialize, and, yes, cultures can emerge – but those cultures might be very thin indeed. Because as Tom points out it’s not just social norms, it’s not just a sense of place, or how we relate to our avatars that matters, it’s that we’ve been handed a tool set and from it, we have the opportunity to extend our journey as virtual humans and through virtuality itself find the gap between it and actuality which represents our potential.

It’s not so much about immersion or augmentation which are debates that I often feel like it misses a deeper point. And I talk about tools a lot, and how I want to push the limits of those tools, whether for collaboration or just to make cooler looking prims.

And maybe Tom has given me the way to think about that, because techne is the paramater that creates that gap, that sense of possibility, because it embodies both the continuum of our virtuality, which began when we first picked up a rock, and it embodies change, that great ride forward into all the profound wonder and understanding, and all the possibilities for both hope and pain that our foundation in techne implies. The companies who use virtual worlds for collaboration will find out soon enough that you can’t just graft old cultures onto new tools, they demand new models. And so they may not become immersionists, but they do become frontierspeople within the wider domain of a culture based on recursive techne and the gap which can be widened by immersion but which is not precluded without it.

Christian can predict the end of Second Life and a whole new range of 3D applications, and all those things are probably true. But simulations or commercial 3D or collaboration environments are not culture – they’re mostly the application of more refined tools to the last generation of cultural norms. Only within virtual worlds like Second Life might we extend the notion of virtuality past sociality, identity and place and deepen our human journey, whether by walking through that space holding hands, rezzing a prim, or meeting those other avatars for a business meeting who are – well, they’re you, and yet they’re not.

We’re not escaping anything. We’re moving forward on the powerful journey of being human. But Rheta is right: we’ve just begun exploring the possibilities.

Welcome to the deepening of the world.

Gosh, now that is a lot to chew on. Bewildered and overwhelmed as I am, I’ll do what I’m best at, and pick out the part I like best (me) to comment on

It is interesting to find myself poster girl for the immersive, non dissociative use of the metaverse. Serves me right, maybe, seeing Chestnut Rau complained about much the same thing about my quote of her post. Maybe I should really start putting a « warning : Devil’s advocate » footnote on those paragraphs.

Ah well, I think I made my point that, yes, although I think this is a perfectly valid way to use the 3D metaverse, and the one that proves immersion has nothing to do whatsoever with the baggage you bring or do not want to bring from your First Life, too, it is a pretty poor, restricted way to use the immense potential this new world offers.It’s like you say : we’re witnessing a cultural change, not just the advent of new tools.

I’m very much looking forward to your next thoughts on this. Until then I’ll say ciao (to be explained shortly on my blog, as well as the rush I’m in).

I think it’s important to formulate what definition of ‘a virtual world’ you use, because Second Life is one of many, and community based virtual world – which I think is quite ironic, is one of applications for an immersive, multi-user, digital platform

I loved Coming of Age in Second Life, but because of the authors background in anthropology, it’s only natural his study focuses on the social relations and implications which doesn’t do entirely justice to the full potential of these platforms (which is obviously why the book is called Coming of Age in Second Life, and not coming of Age in Virtual Worlds), and is the point Christian argues in which I find him being spot on.

Other than that I feel you raise more than a few excellent points (I think there is a lot, a LOT, to the point you bring up about culture – which is exactly why I’ve been wanting to talk to you ‘face to face’) and give them great context here. Absolutely one of the most interesting articles I’ve red so far.

Digado – I agree, Christian IS spot on. EXCEPT for the part where he’s dismissive of 3D walled gardens. And sure I’m speaking partially through an anthropologists lens when I say that culture carries with it a deeper immersion, something that can keep a world running long after it might have faded off into the sunset. Look at Disney’s Magic Kingdom or Myst Online – both had cultures of sorts, and while the owners pulled the plugs there were still societies there. Really, what that points to is whether Linden can continue to make MONEY not whether the user base will run off en masse to openSim. Once a culture is established it can be pretty hard to uproot.

And Rheta – I don’t think you’re a poster girl for immersion, but I do have you on my wall as a towering thinker. However, you are arguing in your post, whether for provocation or devil’s advocacy that SL provides escape, and I think the point of my post is that I agree with you, albeit from a slightly different angle. Virtual worlds are virtual worlds because of the disconnect they cause from the actual, Tom would say (I think, I’m sure projecting a lot here!), and because they allow us a new way to express sociality.

However, you are arguing in your post, whether for provocation or devil’s advocacy that SL provides escape, and I think the point of my post is that I agree with you, albeit from a slightly different angle. Virtual worlds are virtual worlds because of the disconnect they cause from the actual, Tom would say (I think, I’m sure projecting a lot here!), and because they allow us a new way to express sociality.

I partly disagree on this last point – is it a virtual world if we have 4 users at opposite ends of the grid spinning prims but never talking to each other? Sure – just a dull one.

But I start to come at this definition of virtual worlds in a different way and one that may be as relevant to brands as it is to users or platform owners or experience developers. And that is that virtual worlds allow sociality, but virtual worlds with “legs” will also create cultures within them. The cultures within them are only possible if the users of those worlds have some ability to craft their own artefacts, their own tools, otherwise it’s a social site sponsored by Coke or whatever. And sure, Coke can learn what kinds of tools most befit it as a cultural icon, but most brands want to be PART of a culture not help to build one.

But the gap between the virtual and the actual doesn’t need to arise solely because we escape our actual lives into a culture, world, place, avatar, etc. It arises because we participate in techne. As Tom says, we are ALREADY virtual and always have been – so if we’re escaping our virtual selves from the actual world into an avatar in virtual world, all you’ve really done is introduced recursion.

What this position allows is an augmentationist to also benefit from the gap. So long as the participant creates a gap between actual and virtual by their participant through an avatar, they have opened the thin wedge of possibility, and by participating in techne are participating not in epistime but extending human potential. Culture would thus seemingly arise in a grid full of augmentationists as much as a grid full of immersionists – the gap might be much tighter when you remove, say, anonymity, but it doesn’t mean that the gap disappears. Participation in techne gives rise to culture, virtuality gives rise to the gap, and it’s the strength of the culture (reinforced rather than ‘blurred’ by the loop between the actual and virtual) and the power of the tools that unleashes our potential.

It seems to me that this makes the tent wide enough for us all. Escape becomes another word for creating a more pronounced gap, and thus more pronounced potential, but it’s not a precondition to that gap occurring – the gap which Tom calls the source of our new possibilities for human being.

I’d also say that while this tent is wide enough to include both a tight coupling of the actual and the virtual, culture, immersion, escape – all that good stuff, it’s not quite wide enough to embrace simulation or 3D commerce. Those are applications of techne, but they’re not recursive.

A game is not recursive. It is not techne as a product of techne – it’s a game, it’s virtual, it can even be cultural. But it’s generally not recursive – it is not techne within it. (It’s interesting, as a side note, to to think about Spore in this context, because it will be recursive, it certainly will contain techne with it, and I wonder whether that doesn’t open up a discussion of whether you need avatars to be present simultaneously to consider it a virtual world, or in this case a virtual universe).

3D commerce is not recursive either – and while a gap can still be created through clever use of avatars, sociality, and perhaps even, to a degree, culture, it doesn’t generally open us up to greater potentials, that wonderful space where we have the tools within the technology itself.

The definition of “virtual world” is broad and wide. I’ll stick (for now, because it deserves far deeper thought, and maybe our discussion Digado!) with a virtual world being a place spawned by technology that is always on and where you have a sense of presence. Where stuff can change and evolve even when you log off.

And sure, that casts a wide net – games, casual game portals with little 2D avatars, or a 3D room on a Facebook profile. But what defines SOME virtual worlds, like Second Life, is that the tools for cultural expression reside with the users rather than the platform owners. Techne within techne is the source of greater possibility. Which would include the former Sims online, openSim, etc. and the subtle differences and power of one platform over another can then be parsed through the power of the tools, our ability to create a larger gap through avatar expression, the abilities for sociality, and the cultural contexts on which the platforms are predicated – cultural capitalism in the case of Second Life. What defines the OpenSim culture, I wonder – Second Life arose from concepts of property and ownership attached to the recursive techne. Is OpenSim’s defined by the lack of these concepts?

None of these things then guarantee a culture, but the way you tweak the buttons and the ‘engine’ will give rise to different cultural outcomes. Thus, my argument in one form or another to introduce greater tools to a platform like Second Life is predicated on the idea that I’d like to see the culture continue to thrive because of the ability for users to deepen their ability to express new cultural artefacts, whether those dividuals doing the expression are companies, scientists, casual users, or escapists.

Having said that, the ability for the culture to thrive and change and grow – for social norms to evolve, for potentials to be expanded, for the gap to be expanded because of the strange loop between the virtual and the actual, is hindered if the society is too closed. Expanding the tool set in a way that raises the barriers to entry doesn’t do anything to help the culture thrive, it just makes the culture insular, and so you end up with the paradoxical argument that we need both more advanced tools and a far simpler way to become a participant.

Before I clutter up your comments with a lengthy response, I wanted to share with you a paper that has me thinking, drinking and rethinking entitled “Virtual Worlds Don’t Exist”.

You can find the pdf here: http://virtual-economy.org/files/Lehdonvirta-VWDE.pdf

Once you’ve had the chance to read it (and maybe you have but I doubt it because you would have likely referenced it) I’d love to continue this discussion in the context of “The Magic Circle”.

Yay! The magic circle!

Will do. And it’s interesting, Tom speaks a lot about the magic circle and blurring of actual and virtual and makes the point that for all the discussion of the “membrane” most people look at it the wrong way. However, I’ll reserve comments for now and thank you for the link!

Thanks for such a thoughtful and juicy post! Although I plead guilty to spending an inordinate amount of time analyzing and theorizing about this stuff, and enjoy this kind of discussion, the Virtual World that can be told is not the eternal Virtual World (to paraphrase Lao Tzu.)

So I wonder if our disagreements stem primarily from mistaking our subjective viewpoints for universal truth. It’s like the old folk tale of the blind men who were asked to describe an elephant through their experience of being next to one part of its body. The person who felt the trunk thought it was a snake. The man at the leg thought it was like a trunk and the unlucky soul who was standing under it’s backside thought it felt like shit.

Personally, I’m rooting for those with all points of view to go after their visions (assuming they aren’t in the take over the world category), because as you said, the tent is wide. Predictions of the future are interesting but almost always off-base. The coolest new things that emerge are unanticipated.

[...] May 2008 · No Comments I was over reading Dusan’s blog and a paper linked in its comments that sent me into a little mental spin. Normally I’d just [...]

[...] My Avatar is Not Me, or, Why Virtual Worlds Will Not Become Appliances My avatar is my interface to a culture, and in this case, the culture in which my avatar performs (just as I perform in the actual world within my own culture) has the unique property that it’s recursive and that its basis is techne – one in which the tool we’ve built in silicon and wire contains the tools within it. Possibly related posts: (automatically generated)Bring Your Avatar Into RL with a 3-D PrinterHatred, Faith and Cultural Identity Posted in Second Life, Second Life Experience, Virtual worlds. Tags: Second Life. [...]

[...] of Culture I’m repeating myself – the premise that it’s culture that gives something longevity. Interaction, technology, [...]

[...] I’m a big fan of Coming of Age in Second Life, the new book by Tom Boellstorff and touched on it recently. [...]

[...] written about Tom’s book previously, and there were engaging discussions on Savage Minds that are worth checking out for both an [...]