Digital Urban is a must-stop blog for me these days, reminding me of the blurring between the real and the virtual, and that the virtual can and will incorporate more real, while the real can “look” more virtual. Um, does that make sense?

Whatever, it’s a reminder that the metaverse includes virtual worlds, augmented reality, mirror worlds, and life-logging.

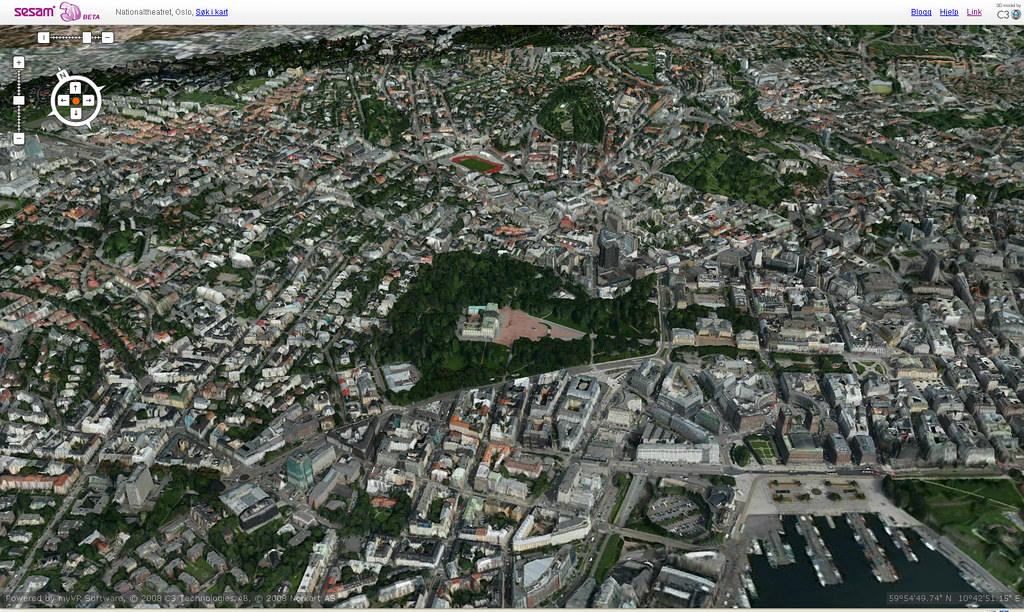

They recently posted about a 3D fly-through of Trondheim, and what struck me about it was that the 3D city was generated procedurally. All of the buildings and their textures generated purely from imagery. I took a fly-through (try it, it’s worth it)…and the camera movements and loading times were impressive.

I took a simple snap of the fly-through:

Trondheim 3D demo in HD from Morten Jacobsen on Vimeo.

Importing Reality

What’s clear from the fly through is that the 3D city is composed of meshes - imagine sculptys made of mega prims. So it occurred to me that there’s no reason models like this shouldn’t be easily imported into Second Life or OpenSim. Not that they aren’t already - I’ve blogged previously about importing real world models and cityscapes into Second Life, but I wonder if we’re just scratching the surface, not only in the use of virtual worlds to mirror real world locations, but in the ability to procedurally generate content.

Over at Mellanium, Joe Rigby and his crew have been using 3D scanners to capture real world objects and have imported them into 3D environments. With this technology in hand, they’ve launched dot Vidi.com, which is setting out to:

“offer an independent web portal for all of the world’s principal heritage. Contributors, stakeholders and advocates worldwide all combine to develop and sustain life and quality in its content. The portal preserves the most important buildings, artefacts and human achievement forever.”

But it’s the 3D scanner technology that’s the kicker - the availability of lower cost machines to scan real world content in order to create 3D models opens a whole range of possibilities. I suppose we could get accurate Neko ears? Or other stuff too I’m sure.

As a proof-of-concept, Mellanium and their partners at Creaform used the highly portable Viuscan device to capture a Chinese mask, with impressive results.

A demo of the scanner:

I Can See It Now

Meantime, the boundaries of data visualization keep pushing further outwards. Digital Urban again was the one to spot this video, brought to us by the good folks at the SenseABLE City Lab at MIT showing “the number of SMS messages sent from Amsterdam in the run up to New Years Eve. With data supplied by KPN Telcom you can see the city almost breath over time with a huge peak at the cross over to New Years Day.”

Amsterdam SMS messages on New Years Eve from Aaron on Vimeo.

I recently interviewed Justin Bovington about his company’s Immersive Workspaces. I was quite taken with his concept of “living landscapes”. He described it as follows:

“And so what we’re trying to do at the moment is to tap into traditional back-end databases and creating visual metaphors in cyberspace. So what happens, the environment itself becomes a living embodiment of the company. And again we call those living landscapes. Pull your mouse out and you can see this wonderful tapestry of data. That’s changing people’s perception of their companies and ways to look at data together and that’s really quite exciting because we’ve only just tapped into that. And arguably that’s going to be a very, very powerful tool.”

The above visualization gives a strong hint of where the merger of data and 3D spaces can take us.

And in the meantime, I still take a fancy to tilt-shift photography, which makes the real seem, well, miniature and virtual, kind of like viewing Second Life on a cell phone maybe.

Flight over Miniature San Francisco (Tilt-Shift) from Inoue_k3D on Vimeo.

Add your comment below, or trackback from your own site.

Subscribe to these comments.